# Load required packages

library(pso) # For PSO implementation (provides psoptim function)

library(ggplot2) # For data visualization

library(dplyr) # For data manipulation and transformation

library(quantmod) # For downloading financial data

library(tidyr) # For reshaping data (pivot_wider, gather functions)

library(plotly) # For creating interactive 3D visualizationsPortfolio Optimization Using PSO

Portfolio optimization represents a critical task in investment management, where the goal involves allocating capital across different assets to maximize returns while controlling risk. This post explores how to use Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) to perform mean-variance portfolio optimization with various constraints.

For additional information on mean-variance optimization and the CAPM model, refer to this paper.

For additional information on particle swarm optimisation, refer to this post on

Libraries

Data Collection

The first step is to gather historical price data to calculate returns and risk metrics.

Getting Stock Tickers

This post uses stocks from the NIFTY50 index, which includes the 50 largest Indian companies by market capitalisation:

# Read ticker list from NSE (National Stock Exchange of India) website

ticker_list <- read.csv("https://raw.githubusercontent.com/royr2/datasets/refs/heads/main/ind_nifty50list.csv")

# View the first few rows

head(ticker_list[,1:3], 5) Company.Name Industry Symbol

1 Adani Enterprises Ltd. Metals & Mining ADANIENT

2 Adani Ports and Special Economic Zone Ltd. Services ADANIPORTS

3 Apollo Hospitals Enterprise Ltd. Healthcare APOLLOHOSP

4 Asian Paints Ltd. Consumer Durables ASIANPAINT

5 Axis Bank Ltd. Financial Services AXISBANKDownloading Historical Price Data

The next step involves downloading historical price data for these stocks using the quantmod package, which provides an interface to Yahoo Finance:

# Append ".NS" to tickers for Yahoo Finance format (NS = National Stock Exchange)

tickers <- paste0(ticker_list$Symbol, ".NS")

tickers <- tickers[!tickers %in% c("ETERNAL.NS", "JIOFIN.NS")]

# Initialize empty dataframe to store all ticker data

ticker_df <- data.frame()

# Create a progress bar to monitor the download process

# pb <- txtProgressBar(min = 1, max = length(tickers), style = 3)

# Loop through each ticker and download its historical data

for(nms in tickers){

# Download data from Yahoo Finance

df <- getSymbols(Symbols = nms, verbose = FALSE, auto.assign = FALSE)

# Rename columns for clarity

colnames(df) <- c("open", "high", "low", "close", "volume", "adjusted")

df$date = rownames(df)

# Convert to dataframe and add ticker and date information

df <- data.frame(df)

df$ticker <- nms

df$date <- rownames(df)

# Append to the main dataframe

ticker_df <- rbind(ticker_df, df)

Sys.sleep(0.2)

# Update progress bar

# setTxtProgressBar(pb, which(tickers == nms))

}

# Reshape data to wide format with dates as rows and tickers as columns

# This format facilitates the calculation of returns across all stocks

prices_df <- pivot_wider(data = ticker_df, id_cols = "date", names_from = "ticker", values_from = "close")

# Remove rows with missing values to ensure complete data

prices_df <- na.omit(prices_df)

# Check the date range of our data

range(prices_df$date)[1] "2017-11-17" "2025-10-07"# Check dimensions (number of trading days × number of stocks + date column)

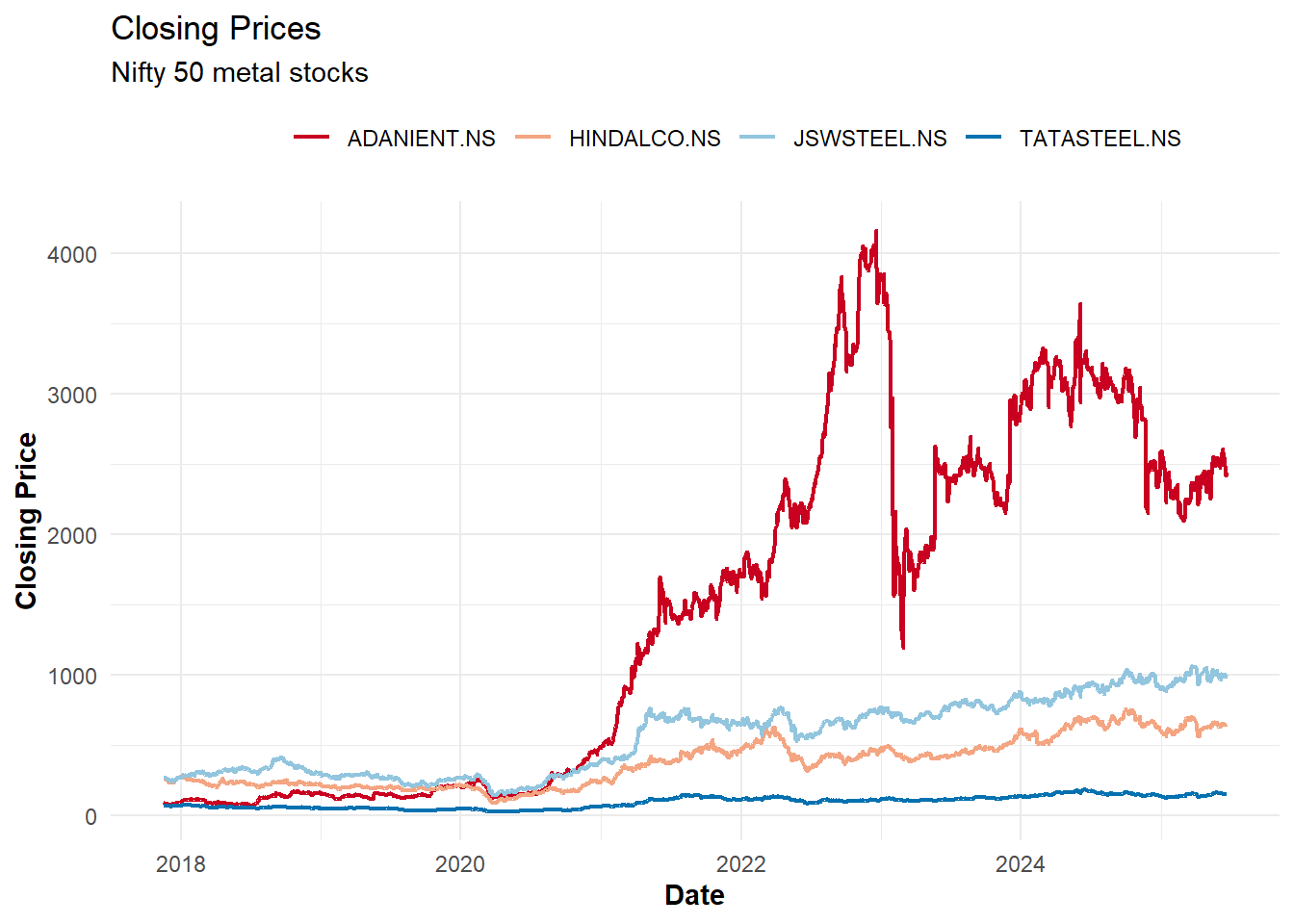

dim(prices_df)[1] 1949 49Visualizing the Data

# Plot closing prices for metal stocks

prices_df %>%

# Convert from wide to long format for easier plotting with ggplot2

pivot_longer(-date, names_to = "ticker", values_to = "price") %>%

# Attach industry information from our original ticker list

left_join(ticker_list %>%

mutate(ticker = paste0(Symbol, ".NS")) %>%

select(ticker, industry = Industry),

by = "ticker") %>%

# Convert date strings to Date objects

mutate(date = as.Date(date)) %>%

# Filter to show only metal industry stocks for clarity

filter(stringr::str_detect(tolower(industry), "metal")) %>%

# Create the line plot

ggplot(aes(x = date, y = price, color = ticker)) +

geom_line(linewidth = 0.8) +

theme_minimal() +

scale_color_brewer(palette = "RdBu") + # Use a color-blind friendly palette

labs(title = "Closing Prices",

subtitle = "Nifty 50 metal stocks",

x = "Date",

y = "Closing Price") +

theme(legend.position = "top",

legend.title = element_text(colour = "transparent"),

axis.title.x = element_text(face = "bold"),

axis.title.y = element_text(face = "bold"))

The visualization demonstrates the price movements of metal stocks over time. The data reveals periods of both correlation and divergence between different stocks, highlighting the importance of diversification in portfolio construction.

Calculating Returns

For portfolio optimization, we need to work with returns rather than prices. Returns better represent the investment performance and have more desirable statistical properties (like stationarity):

# Calculate daily returns for all stocks

# Formula: (Price_today / Price_yesterday) - 1

returns_df <- apply(prices_df[,-1], 2, function(vec){

ret <- vec/lag(vec) - 1 # Simple returns calculation

return(ret)

})

# Convert to dataframe for easier manipulation

returns_df <- as.data.frame(returns_df)

# Remove first row which contains NA values (no previous day to calculate return)

returns_df <- returns_df[-1,]

# Pre-compute average returns and covariance matrix for optimization

# These constitute key inputs to the mean-variance optimization

mean_returns <- sapply(returns_df, mean) # Expected returns

cov_mat <- cov(returns_df) # Risk (covariance) matrixThe mean returns represent expectations for each asset’s performance, while the covariance matrix captures both the individual volatilities and the relationships between assets. These serve as inputs to the optimization process.

Portfolio Optimization Framework

Objective Function

In mean-variance optimisation the objective function, which defines the optimization target balances three key components:

- Expected returns (reward): The weighted average of expected returns for each asset

- Portfolio variance (risk): A measure of the portfolio’s volatility, calculated using the covariance matrix

- Risk aversion parameter: Controls the trade-off between risk and return (higher values prioritize risk reduction)

The implementation also incorporates constraints through penalty terms:

obj_func <- function(wts,

risk_av = 10, # Risk aversion parameter

lambda1 = 10, # Penalty weight for full investment constraint

lambda2 = 1e2, # Reserved for additional constraints

ret_vec, cov_mat){

# Calculate expected portfolio return (weighted average of asset returns)

port_returns <- ret_vec %*% wts

# Calculate portfolio risk (quadratic form using covariance matrix)

port_risk <- t(wts) %*% cov_mat %*% wts

# Mean-variance utility function: return - risk_aversion * risk

# This is the core Markowitz portfolio optimization formula

obj <- port_returns - risk_av * port_risk

# Add penalty for violating the full investment constraint (sum of weights = 1)

# The squared term ensures the penalty increases quadratically with violation size

obj <- obj - lambda1 * (sum(wts) - 1)^2

# Return negative value since PSO minimizes by default, but the goal is to maximize

# the objective (higher returns, lower risk)

return(-obj)

}This objective function implements the classic mean-variance utility with a quadratic penalty for the full investment constraint. The risk aversion parameter allows us to move along the efficient frontier to find portfolios with different risk-return profiles.

Two-Asset Example

Before tackling the full portfolio optimization problem, this section begins with a simple two-asset example. This approach helps visualize how PSO works and validates the methodology:

# Use only the first two assets for this example

# Calculate their average returns and covariance matrix

mean_returns_small <- apply(returns_df[,1:2], 2, mean)

cov_mat_small <- cov(returns_df[,1:2])

# Define a custom PSO optimizer function to track the optimization process

pso_optim <- function(obj_func,

c1 = 0.05, # Cognitive parameter (personal best influence)

c2 = 0.05, # Social parameter (global best influence)

w = 0.8, # Inertia weight (controls momentum)

init_fact = 0.1, # Initial velocity factor

n_particles = 20, # Number of particles in the swarm

n_dim = 2, # Dimensionality (number of assets)

n_iter = 50, # Maximum iterations

upper = 1, # Upper bound for weights

lower = 0, # Lower bound for weights (no short selling)

n_avg = 10, # Number of iterations for averaging

...){

# Initialize particle positions randomly within bounds

X <- matrix(runif(n_particles * n_dim), nrow = n_particles)

X <- X * (upper - lower) + lower # Scale to fit within bounds

# Initialize particle velocities (movement speeds)

dX <- matrix(runif(n_particles * n_dim) * init_fact, ncol = n_dim)

dX <- dX * (upper - lower) + lower

# Initialize personal best positions and objective values

pbest <- X # Each particle's best position so far

pbest_obj <- apply(X, 1, obj_func, ...) # Objective value at personal best

# Initialize global best position and objective value

gbest <- pbest[which.min(pbest_obj),] # Best position across all particles

gbest_obj <- min(pbest_obj) # Best objective value found

# Store initial positions for visualization

loc_df <- data.frame(X, iter = 0, obj = pbest_obj)

iter <- 1

# Main PSO loop

while(iter < n_iter){

# Update velocities using PSO formula:

# New velocity = inertia + cognitive component + social component

dX <- w * dX + # Inertia (continue in same direction)

c1*runif(1)*(pbest - X) + # Pull toward personal best

c2*runif(1)*t(gbest - t(X)) # Pull toward global best

# Update positions based on velocities

X <- X + dX

# Evaluate objective function at new positions

obj <- apply(X, 1, obj_func, ...)

# Update personal bests if new positions are better

idx <- which(obj <= pbest_obj)

pbest[idx,] <- X[idx,]

pbest_obj[idx] <- obj[idx]

# Update global best if a better solution is found

idx <- which.min(pbest_obj)

gbest <- pbest[idx,]

gbest_obj <- min(pbest_obj)

# Store current state for visualization

iter <- iter + 1

loc_df <- rbind(loc_df, data.frame(X, iter = iter, obj = pbest_obj))

}

# Return optimization results

lst <- list(X = loc_df, # All particle positions throughout optimization

obj = gbest_obj, # Best objective value found

obj_loc = gbest) # Weights that achieved the best objective

return(lst)

}

# Run the optimization for our two-asset portfolio

out <- pso_optim(obj_func,

ret_vec = mean_returns_small, # Expected returns

cov_mat = cov_mat_small, # Covariance matrix

lambda1 = 10, risk_av = 100, # Constraint and risk parameters

n_particles = 100, # Use 100 particles for better coverage

n_dim = 2, # Two-asset portfolio

n_iter = 200, # Run for 200 iterations

upper = 1, lower = 0, # Bounds for weights

c1 = 0.02, c2 = 0.02, # Lower influence parameters for stability

w = 0.05, init_fact = 0.01) # Low inertia for better convergence

# Verify that the weights sum to approximately 1 (full investment constraint)

sum(out$obj_loc)[1] 0.9891172In this implementation, the tracking of all particle movements throughout the optimization process occurs. This enables visualization of how the swarm converges toward the optimal solution.

Visualizing the Optimization Process

One advantage of starting with a two-asset example is the ability to visualize the entire search space and observe how the PSO algorithm explores it. The following creates a 3D visualization of the objective function landscape and the path each particle took during optimization:

# Create a fine grid of points covering the feasible region (all possible weight combinations)

grid <- expand.grid(x = seq(0, 1, by = 0.01), # First asset weight from 0 to 1

y = seq(0, 1, by = 0.01)) # Second asset weight from 0 to 1

# Evaluate the objective function at each grid point to create the landscape

grid$obj <- apply(grid, 1, obj_func,

ret_vec = mean_returns_small,

cov_mat = cov_mat_small,

lambda1 = 10, risk_av = 100)

# Create an interactive 3D plot showing both the objective function surface

# and the particle trajectories throughout the optimization

p <- plot_ly() %>%

# Add the objective function surface as a mesh

add_mesh(data = grid, x = ~x, y = ~y, z = ~obj,

inherit = FALSE, color = "red") %>%

# Add particles as markers, colored by iteration to show progression

add_markers(data = out$X, x = ~X1, y = ~X2, z = ~obj,

color = ~ iter, inherit = FALSE,

marker = list(size = 2))This visualization demonstrates:

- The objective function landscape as a 3D surface

- The particles (small dots) exploring the search space

- How the swarm converges toward the optimal solution over iterations (color gradient)

The concentration of particles in certain regions indicates where the algorithm found promising solutions. The global best solution represents where the particles ultimately converge.

Multi-Asset Portfolio Optimization

To scale the problem to multiple assets, instead of using the custom PSO implementation, this section leverages the psoptim function from the pso package:

# Get the number of stocks in the dataset

n_stocks <- ncol(returns_df)

# Run the PSO optimization for the full portfolio

opt <- psoptim(

# Initial particle positions (starting with equal weights)

par = rep(0, n_stocks),

# Objective function to minimize

fn = obj_func,

# Pass the expected returns and covariance matrix

ret_vec = mean_returns,

cov_mat = cov_mat,

# Set constraint parameters

lambda1 = 10, # Weight for full investment constraint

risk_av = 1000, # Higher risk aversion for a more conservative portfolio

# Set bounds for weights (no short selling allowed)

lower = rep(0, n_stocks),

upper = rep(1, n_stocks),

# Configure the PSO algorithm

control = list(

maxit = 200, # Maximum iterations

s = 100, # Swarm size (number of particles)

maxit.stagnate = 500 # Stop if no improvement after this many iterations

)

)

# Calculate and display the expected return of the optimized portfolio

paste("Portfolio returns:", round(opt$par %*% mean_returns, 5))[1] "Portfolio returns: 0.00058"# Calculate and display the standard deviation (risk) of the optimized portfolio

paste("Portfolio Std dev:", round(sqrt(opt$par %*% cov_mat %*% opt$par), 5))[1] "Portfolio Std dev: 0.00871"# Verify that the weights sum to approximately 1 (full investment constraint)

sum(opt$par)[1] 0.9958314Adding Tracking Error Constraint

Tracking error measures how closely a portfolio follows a benchmark.

# Define benchmark portfolio (equally weighted across all stocks)

bench_wts <- rep(1/n_stocks, n_stocks)

# Calculate the time series of benchmark returns

bench_returns <- as.matrix(returns_df) %*% t(t(bench_wts))

# Create a new objective function that includes tracking error

obj_func_TE <- function(wts,

risk_av = 10, # Risk aversion parameter

lambda1 = 10, # Full investment constraint weight

lambda2 = 50, # Tracking error constraint weight

ret_vec, cov_mat){

# Calculate portfolio metrics

port_returns <- ret_vec %*% wts # Expected portfolio return

port_risk <- t(wts) %*% cov_mat %*% wts # Portfolio variance

port_returns_ts <- as.matrix(returns_df) %*% t(t(wts)) # Time series of portfolio returns

# Original mean-variance objective

obj <- port_returns - risk_av * port_risk

# Full investment constraint (weights sum to 1)

obj <- obj - lambda1 * (sum(wts) - 1)^2

# Tracking error constraint (penalize deviation from benchmark)

# Tracking error is measured as the standard deviation of the difference

# between portfolio returns and benchmark returns

obj <- obj - lambda2 * sd(port_returns_ts - bench_returns)

return(-obj) # Return negative for minimization

}

# Run optimization with the tracking error constraint

opt <- psoptim(

# Initial particle positions

par = rep(0, n_stocks),

# Use our new objective function with tracking error

fn = obj_func_TE,

# Pass the expected returns and covariance matrix

ret_vec = mean_returns,

cov_mat = cov_mat,

# Set constraint parameters

lambda1 = 10, # Weight for full investment constraint

risk_av = 1000, # Risk aversion parameter

# Set bounds for weights

lower = rep(0, n_stocks),

upper = rep(1, n_stocks),

# Configure the PSO algorithm

control = list(

maxit = 200, # Maximum iterations

s = 100, # Swarm size

maxit.stagnate = 500 # Stop if no improvement after this many iterations

)

)

# Calculate and display the expected return of the optimized portfolio

paste("Portfolio returns:", round(opt$par %*% mean_returns, 5))[1] "Portfolio returns: 0.00072"# Calculate and display the standard deviation (risk) of the optimized portfolio

paste("Portfolio Std dev:", round(sqrt(opt$par %*% cov_mat %*% opt$par), 5))[1] "Portfolio Std dev: 0.0109"# Verify that the weights sum to approximately 1

sum(opt$par)[1] 0.9958513Adding the tracking error constraint, not only balances risk and return but also tracks the performance of an equally-weighted benchmark. The lambda2 parameter controls the closeness of benchmark tracking - higher values result in portfolios that more closely resemble the benchmark.

Advantages and Limitations of PSO

Advantages:

Flexibility: PSO can handle non-convex, non-differentiable objective functions, making it suitable for complex portfolio constraints that traditional optimizers struggle with

Simplicity: The algorithm is intuitive and relatively easy to implement compared to other global optimization techniques

Constraints: Various constraints can be easily incorporated through penalty functions without reformulating the entire problem

Global Search: PSO explores the search space more thoroughly and is less likely to get stuck in local optima compared to gradient-based methods

Parallelization: The algorithm is naturally parallelizable, as particles can be evaluated independently

Limitations:

Variability: Results can vary between runs due to the stochastic nature of the algorithm, potentially leading to inconsistent portfolio recommendations

Parameter Tuning: Performance significantly depends on parameters like inertia weight and acceleration coefficients, which may require careful tuning

Convergence: There’s no mathematical guarantee of convergence to the global optimum, unlike some convex optimization methods

Computational Cost: Can be computationally intensive for high-dimensional problems with many assets

Constraint Handling: While flexible, the penalty function approach may not always satisfy constraints exactly

Practical Applications

PSO-based portfolio optimization proves particularly valuable in scenarios where:

- Traditional quadratic programming approaches fail due to complex constraints

- The objective function includes non-linear terms like higher moments (skewness, kurtosis)

- Multiple competing objectives need to be balanced

- The portfolio needs to satisfy regulatory or client-specific constraints

The approach demonstrated in this post can be extended to include additional constraints such as:

- Sector or industry exposure limits

- Maximum position sizes

- Turnover or transaction cost constraints

- Risk factor exposures and limits

- Cardinality constraints (limiting the number of assets)